There is a scene in the film “Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets” in which the sleek and wealthy Lucius Malfoy insults the Weasley family, sneering at their lack of wealth and disparaging their friendship with “muggles” (non-wizards). In summary, Mr. Malfoy asks, “What is the use of being a disgrace to the name of ‘wizard’ if they don’t even pay you well for it?” To which Mr. Weasley responds, “We have a very different idea of what disgraces the name of ‘wizard,’ Malfoy.”

I was reminded of this scene this morning after reading a few things on the internet about the US Presidential election, and having a chat with my husband about a YouTube channel run by Todd Friel. The crux of the matter is the word “biblical.” In two separate internet spaces I encountered an individual (identifying himself as American and Christian) who was describing certain views or values as “biblical” and offering no explanation of the term or even reference to relevant verses.

For example, a certain poster on Facebook would appear to think that voting for Mr. Trump is “more in line with the Constitution promoting religious freedom, the value of human life, and Biblical values.” (I’ll pass over the question of what the Constitution has to do with “Biblical values,” although I think it is a highly pertinent one for US Christians to think through.) This man clearly feels that Trump is the lesser of two evils because a government under Hilary Clinton “would be the most pro-abortion, immoral, anti-Evangelical, anti-capitalist, pro-terrorist group of leaders in American History.” Given my roots in conservative Christian America, what I read here is a man who is determined not to vote for Hilary because her government would allow abortion and equal marriage to continue to be the law of the land. As an aside, how on earth this man can think that Mr. Trump’s platform will “promote religious freedom” in ANY way is utterly beyond me. This is a man who has called for the exclusion and registration of Muslims based on nothing more than their religion. If anything, the man is a threat to religious freedom. I’m not pro-Clinton, but the argument here in favour of Mr. Trump is laughable.

And what is the definition of “biblical” in this context? Constitutional? anti-abortion? Christian hegemony? anti-gay? I’m struggling to see a viable connection.

In the other instance Mr. Friel is presenting a piece to camera about the “biblical” guidance about owning a home in response to the rise of the “Tiny House Movement.” He says there are 21 biblical principles about owning a home, but only shares five of them. He uses no direct references to the Bible in any form, but spends a lot of time talking about how the outward actions are unimportant because it is what is in the heart that matters. Perhaps he is thinking of 1 Samuel 16:7 here: “the Lord looks upon the heart,” or perhaps Matthew 23:27 which emphasises that it is more important what is the inner reality rather than the outward appearance.

However he does not appear to consider those scriptures that remind us of the importance of actions and words as indicators of what is going on in our hearts: (Matt 12:34, Luke 6:45, James 2:14-26, Galatians 6: 7-8). Perhaps it is true that we shouldn’t expect one change in our outer lives to change our inner reality, but it is certainly true that making outward changes can, and will, effect our inner reality in some way.

The point is, just as Mr. Malfoy and Mr. Weasley had profoundly different ideas about “what disgraces the name of wizard,” those who identify as Christian also have profoundly different ideas of what is “biblical” and what is not. The internet allows us to encounter more and more ideas and interpretations of faith, and it is sad, not to say disingenuous, that there are people out there who still think it is acceptable to present their particular tradition’s interpretation of Christianity as truly “biblical” without so much as explaining what it is or where it came from!

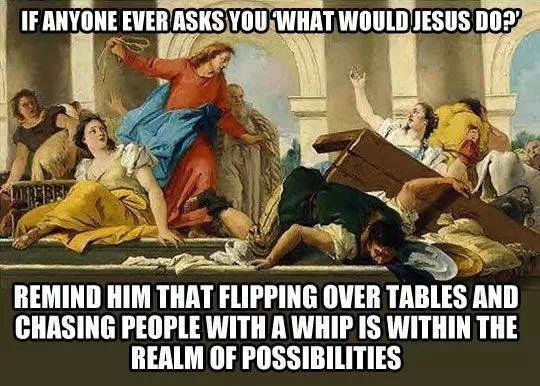

The truth is that the Bible can be made to support almost any point of view or doctrine if certain parts are emphasised over other parts. The parts you emphasise determine the beliefs you see as central, and the method of interpretation (contextual, historical/critical, “literal”) effects the meaning of the words. Also your objective or subjective beliefs about the Bible will effect what amount of authority you give scriptures and why.

All of these things feed into the meaning of the word “biblical,” and it is naive at best and severely arrogant at worst to use the word with no context or explanation as some kind of proof-stamp that the writer/speaker has the “truth” all sown up.

There are some who have a very different idea of what “biblical” means, so much so as to make it seem we are worshiping different gods – or at least reading different Bibles. Don’t underestimate the importance of context, point of view and assumptions, and please don’t dismiss the differing opinions of others as ‘unbiblical’ just because they aren’t the same as yours.